In previous articles on running form, I focused on the role the hip abductors—gluteus medius and gluteus minimus—play as lateral stabilizers (article 1 | article 2). In this article, I shift the focus to the other glutes—namely, the gluteus maximus.

The glute max, along with the hamstrings, act as primary hip extensors. And each step you take while running involves extension of the hips. In today’s world dominated by sitting, it is easy for the glutes to become neglected and underused. As a result, it is not uncommon for runners to shift the burden of hip extension onto the hamstrings. This is bad news because runners who rely on their hamstrings at the expense of the glute max give up a great deal of efficiency—not to mention increase the potential for injury.

Although the hamstrings and glute max are both effective at extending the hips during running, the hamstrings are comprised of a greater percentage of fast-twitch muscle fibers whereas the glute max contains a greater percentage of slow-twitch muscle fibers. Slow-twitch fibers excel at long duration activities—like extending your hip step after step while running long distances. The glute max, like the Energizer Bunny, is better equipped for the long haul.

In addition, the glute max is a far more powerful muscle than the hamstring. With these characteristics, the glute max is crucial to maintaining the pelvis in a stable, neutral position while running—or while walking or simply standing for that matter.

Recall the article on running posture. Key to that discussion was maintaining a tall body with a slight forward lean. Instability in the core can easily disrupt this posture, which is why effective runners must possess a strong core.

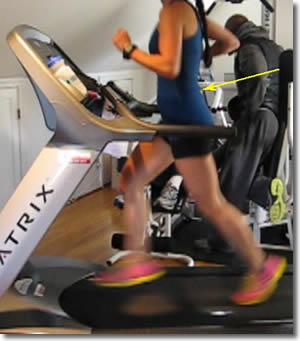

The runner in the image at the right has an excessive lumbar arch while running. This means the pelvis is tilted forward, which overlengthens the hamstrings. When the glute max clocks out or fails to report for duty, the hamstrings are not only left to carry the burden of hip extension, but they are asked to do this in an overlengthened state as a result of the anterior pelvic tilt. This can be a pain in the butt or hamstring—quite literally. In fact, this runner has been dealing with hamstring and glute niggles. And the video analysis also showed a lack of full extension in the latter half of her stride.

To eliminate the excessive lumbar arch, the runner will want to focus on increasing the flexibility of the hip flexors along with work that strengthens and cues the deep abdominals (transversus abdominis) and glute max. Through the functional strength exercises and muscle activation cues recommended below, the aim is for the runner to feel more like she is “running from the butt” with the glute max initiating each step.

Since half of this neuromuscular work is about making the muscles smarter—that is, firing when needed—and not just stronger, it will also be helpful to cue the deep abdominals and glutes throughout the day while walking and standing during everyday activities (especially after long periods of sitting). This will help “retrain” the core muscles necessary for good posture and economical running.

Functional Strength Exercises

- Front planks to target deep abdominals

- Glute bridge, donkey kicks and other exercises that strengthen and cue the glute max

- Advance to leg raises from front plank position as an alternative to the above

Muscle Activation Cues

- Perform a minute or two of front plank before running to cue and engage deep abdominals

- Perform a few sets of donkey kicks before running to cue and engage glute max

- Neuromuscular activation exercises that cue the glute max