Athletes can be hard on themselves. Have you ever finished a race or training session with words of self-criticism flowing through your inner dialogue? If so, you’re not alone. The culture of sport often revolves around the assumption that harsh criticism is necessary to motivate athletes in the face of poor performance.

A growing body of research in psychology, however, has demonstrated that self-compassion — not self-criticism — is the key to developing resilience and improving athletic performance while also enhancing your overall well-being.

A recent study by Ashley Kuchar, Kristin Neff, and Amber Mosewich (2023) details the results of a program they developed and implemented with college athletes called Resilience and Enhancement in Sport, Exercise, & Training (RESET). RESET was adapted from the Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC) program originally developed by Neff and Christopher Germer (Neff & Germer 2013, Germer & Neff 2019). Since the development of MSC, research has shown the effectiveness of “self-compassion-based interventions across a range of outcomes and diverse populations” (Ferrari et al. 2019; see also, Neff et al. 2018, Phillips & Hine 2021, Zessin et al. 2015).

Athletes who participated in the RESET program “experienced greater increases in self-compassion, decreases in self-criticism and fear of self-compassion, and greater improvements in perceived performance” (Kuchar et al. 2023, p. 1). The researchers conclude, “RESET stands to support student-athlete compassion, well-being, and performance by helping athletes and coaches learn to productively respond to adversity and failure, rather than merely reacting to it” (Kuchar et al. 2023, p. 8).

So what is self-compassion and how can you develop this skill to positively impact your own athletic performance and overall well-being?

What is Self-Compassion?

Psychologist Kristin Neff, who pioneered the academic study of self-compassion, defines it as “compassion for the experience of suffering turned inward” — in other words, self-compassion is “how we relate to ourselves in instances of perceived failure, inadequacy, or personal suffering” (Neff 2023, p. 194).

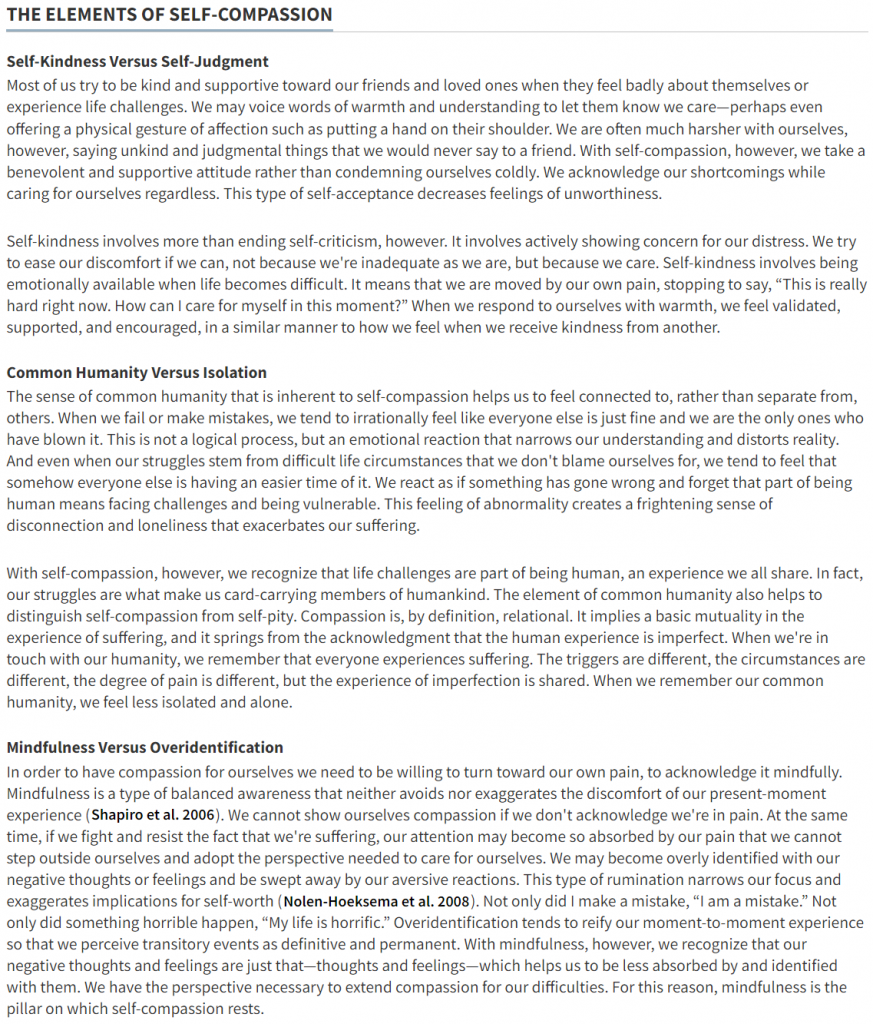

Neff’s model of self-compassion consists of three sets of overlapping domains where each domain represents a continuum with distinct opposites on either end. These elements of self-compassion are:

- Self-Kindness vs. Self-Judgment. Self-kindness involves treating oneself with warmth, acknowledging shortcomings, and actively showing concern for one’s distress, while self-judgment entails being harsh, critical, and unkind to oneself, often using language and attitudes that would never be directed toward a friend.

- Common Humanity vs. Isolation. Common humanity emphasizes the shared experience of suffering and life challenges among all individuals, fostering a sense of connection, while isolation is the feeling that one is uniquely burdened by difficulties, leading to disconnection and loneliness.

- Mindfulness vs. Overidentification. Mindfulness involves acknowledging our pain without avoiding or exaggerating it, maintaining a balanced awareness of our discomfort, while overidentification refers to becoming overly absorbed by negative thoughts and feelings, leading to the perception that transient events are permanent.

What Self-Compassion Is Not

Neff explains that we often have misgivings about self-compassion. “Western culture has doubts about the value of self-compassion, and it generally does not promote it as a virtue. Common misgivings about self-compassion are that it is weak, self-indulgent, and selfish and will undermine motivation (Robinson et al. 2016).” But contrary to the popular misgivings, “the empirical evidence demonstrates that most of the fears people have about self-compassion are misplaced.” (Neff 2023, p. 201)

Neff emphasizes the following points about self-compassion:

- Self-Compassion Makes One Strong, Not Weak. Self-compassion leads to greater resilience in the face of adversity, allowing you to harness failures as growth opportunities.

- Self-Compassion Leads to Health, Not Self-Indulgence. Self-compassion moves you away from harmful and toward healthy behaviors, even increasing physical health in addition to mental resilience.

- Self-Compassion Is Not Selfish and Helps One Care for Others. Self-compassion opens up space so you can be more compassionate toward others.

- Self-Compassion Enhances Rather than Undermines Motivation. Self-compassion, much more than self-criticism, motivates you to improve.

This last point is worth elaborating on in more detail in contrast to the common fallacy in sport that harsh criticism is necessary to motivate athletes.

Self-Compassion Enhances Motivation

In contrast to self-criticism, self-compassion “is an important source of motivation that stems from care and the desire for the self’s well-being rather than from fear of inadequacy” (Neff 2023, p. 204).

Those who practice self-compassion demonstrate greater intrinsic motivation to learn and grow, aiming for high performance standards while also recognizing that high standards cannot always be met. The association between self-compassion and a growth mindset helps those individuals turn setbacks and failures into opportunities for improvement. They have less fear of failure and greater confidence, leaving them more likely to try again when faced with difficulties.

Practicing self-compassion rather than self-criticism also avoids the negative consequences that come with self-criticism, including anxiety, procrastination, negative affect, and self-sabotaging behaviors. Self-compassionate individuals find more personal meaning in their goals, an important aspect of motivation.

Self-Compassion vs. Self-Esteem

Self-compassion is different from the concept of self-esteem in important ways. “While self-esteem is important for good mental health, there are potential problems with the pursuit of self-esteem” (Neff 2023, p. 200). Since self-esteem revolves around judgments and evaluations in assessing one’s performance, it fluctuates based on recent successes or failures (Kernis 2005). The pursuit of self-esteem often leads to the need to stand out from others — to be better than others. As such, it has been associated with “narcissism, inflated and unrealistic self-views, prejudice, and bullying behavior [Crocker & Park 2004]” (Neff 2023, p. 200).

Self-compassion, rather than revolving around judgments or evaluations, allows one to relate to experiences with kindness and acceptance. “Self-compassion does not require feeling better than anyone else, it simply requires acknowledging the shared and imperfect human condition. Research suggests that self-compassion offers similar mental health benefits as those of self-esteem, but without its potential downsides” (Neff 2023, p. 200). Self-compassion can help one better cope with stress than self-esteem.

How to Develop Self-Compassion

The good news is that self-compassion, like other mental skills, can be learned, practiced, and developed. The recent RESET program for college athletes illustrates that anyone can benefit from cultivating greater self-compassion; and those with “the most room for growth” may see the greatest gains (Kuchar, Neff & Mosewich 2023).

A good place to start is to take the self-compassion test on Dr. Neff’s website to determine your current level of self-compassion and identify areas to improve. Then explore some of the exercises and other resources on her website, work through The Mindful Self-Compassion Workbook, or look into the courses offered by the Center for Mindful Self-Compassion.

Central to developing this mental skill is cultivating awareness of when your self-talk involves self-criticism and shifting to self-compassion instead.

Try this:

- Before, during or after your next workout or race, tune into your inner dialogue and notice when you use self-criticism as a motivator. Are there particular traits you criticize about yourself (for example, not having the speed for a fast finishing kick)?

- Once you regularly notice those instances of self-criticism, reflect on how you would respond to a friend who said those things. What language would you use or message would you convey to show compassion to that friend in those situations?

- Now reframe your inner dialogue in those situations to convey that same message of compassion to yourself. Do this each time you recognize yourself using self-criticism during a bad workout or after a poor performance.

To apply self-compassion in these instances, think about the three elements of self-compassion as you formulate your inner dialogue:

- Self-Kindness. Show concern for your distress and struggles.

- Common Humanity. Recognize that struggles are part of being human.

- Mindfulness. Acknowledge but don’t overly identify with those struggles.

Habits of mind — whether positive or negative — are built upon consistent practice. The key is to recognize when those habits are negative and practice the positive habits instead. When it comes to sports performance and well-being in life, self-compassion is one of the most important mental habits you can cultivate. This is because, as Yale psychologist Laurie Santos says in the video below, “Treating yourself like a friend is the way to perform better.”

Yale psychologist Laurie Santos discusses the work on self-compassion by University of Texas psychologist Kristin Neff starting at 2:38 into this video.

References

Crocker J. & Park, L.E. 2004. “The costly pursuit of self-esteem.” Psychological Bulletin 130(3): 392-414. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.392

Ferrari, M., Hunt, C., Harrysunker, A., Abbott, M.J., Beath, A.P., & Einstein, D.A. 2019. “Self-Compassion Interventions and Psychosocial Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of RCTs.” Mindfulness 10(8): 1455–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01134-6

Finlay-Jones, A., Bluth, K., & Neff, K. (eds.). 2023. Handbook of Self-Compassion. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22348-8

Germer, C., & Neff, K. 2019. Teaching the Mindful Self-Compassion Program: A guide for Professionals. Guilford Publications.

Kernis, M.H. 2005. “Measuring self-esteem in context: The importance of stability of self-esteem in psychological functioning.” Journal of Personality Assessment 73: 1569–605. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.392

Kuchar, A.L., Neff, K.D., & Mosewich, A.D. 2023. “Resilience and Enhancement in Sport, Exercise, & Training (RESET): A brief self-compassion intervention with NCAA student-athletes.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 67: 102426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2023.102426

Mosewich, A.D., Ferguson, L.J., & Sereda, B.J. 2023. “Self-Compassion in Competitive Sport.” In A. Finlay-Jones, K. Bluth, & K. Neff (eds.), Handbook of Self-Compassion (pp. 213–230). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22348-8_13

Neff, K D. 2023. “Self-Compassion: Theory, Method, Research, and Intervention.” Annual Review of Psychology 74(1): 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031047

Neff, K D., & Germer, C. K. 2013. “A Pilot Study and Randomized Controlled Trial of the Mindful Self-Compassion Program.” Journal of Clinical Psychology 69(1): 28–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21923

Neff, K.D.; Long, P., Knox, M., Davidson, O., Kuchar, A., Costigan, A., Williamson, Z., Rohleder, N., Tóth-Király, I., and Breines, J.G. 2018. “The forest and the trees: Examining the association of self-compassion and its positive and negative components with psychological functioning.” Self Identity 17(6): 627–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2018.1436587

Phillips, W.J. & Hine, D.W. 2021. “Self-compassion, physical health, and health behavior: A meta-analysis.” Health Psychology Review 15(1): 113–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2019.1705872

Robinson, K.J., Mayer, S., Allen, A.B., Terry, M., Chilton, A., and Leary, M.R. 2016. Resisting self-compassion: Why are some people opposed to being kind to themselves? Self Identity 15(5): 505–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298868.2016.1160952

Zessin, U., Dickhauser, O., and Garbade, S. 2015. “The relationship between self-compassion and well-being: A meta-analysis.” Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being 7(3): 340–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12051