Now that you have some background on the concept of periodization, the different training phases, and the workout types used in those training phases, it’s time to create a custom training plan for your specific goals. Follow the steps below to create your own training plan.

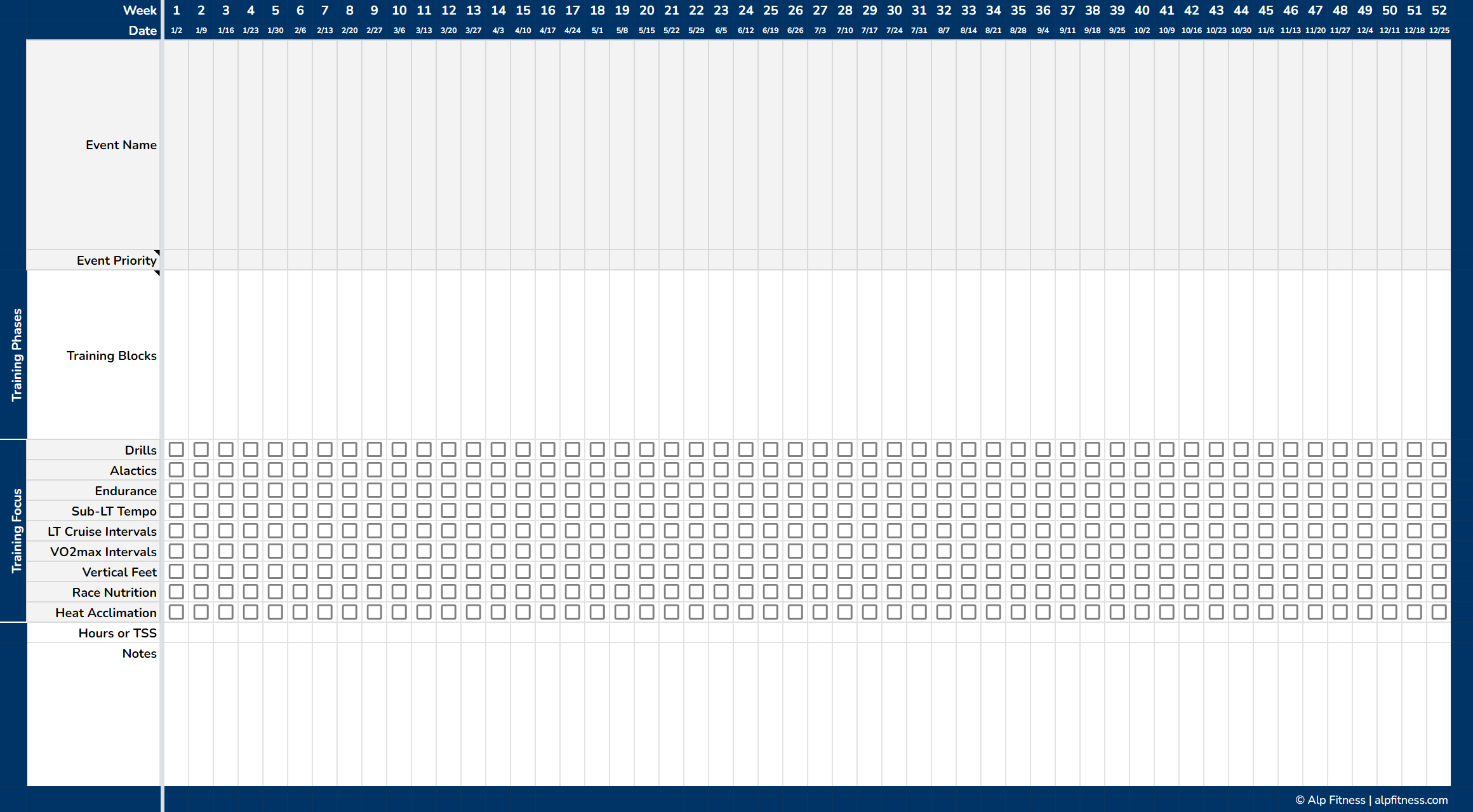

You will use the Alp Fitness training plan template to develop your own custom plan. The template is a Google Sheet. Open the Google Sheet link for the template and make a copy to edit (you can either download it to your computer or save a copy in your own Google Drive).

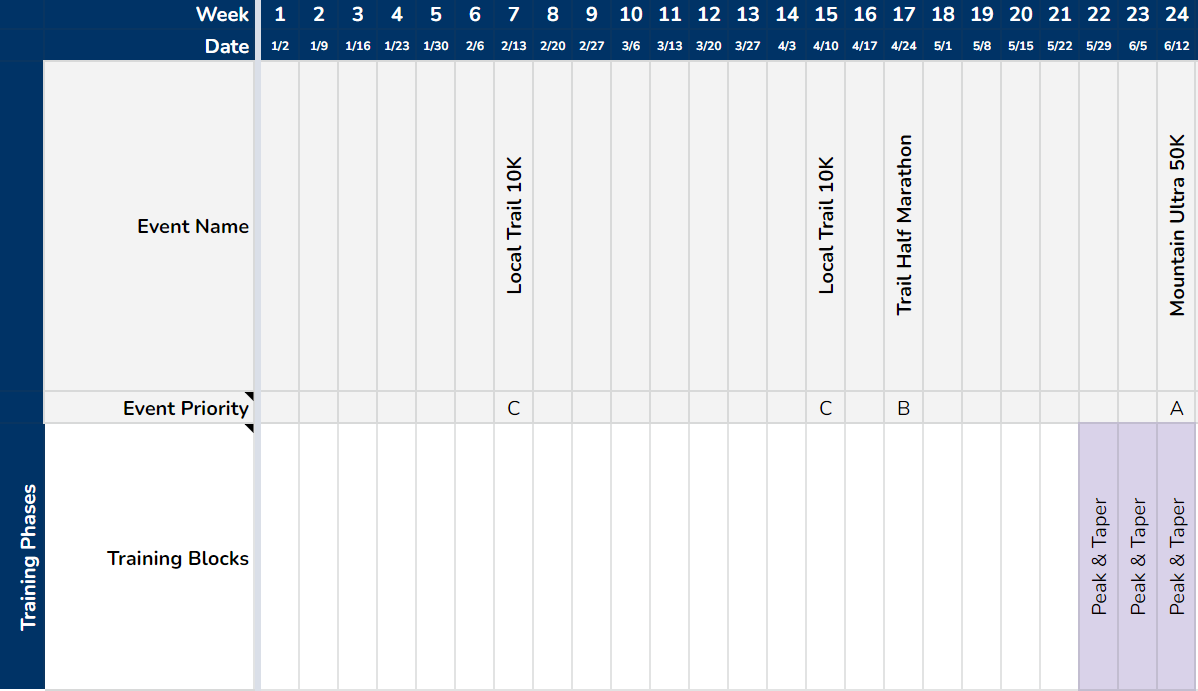

To create a roadmap that guides you toward your destination, start with a high-level calendar view of the training year, as seen in the screenshot below.

Although this template lists a full calendar year — and outlining your training on an annual basis is useful for maximizing your long-term development — you can adapt the template to outline a training plan of any length.

If you only have 12 weeks between now and your target event, then your training plan will be 12 weeks long. If you have six months, then your training plan will be 6 months long, and so on.

Adjust the number of weeks and dates at the top to represent how you organize your training year or competitive seasons, which may differ from a regular calendar year — for example, your training plan might start in early December for an A-priority event in May.

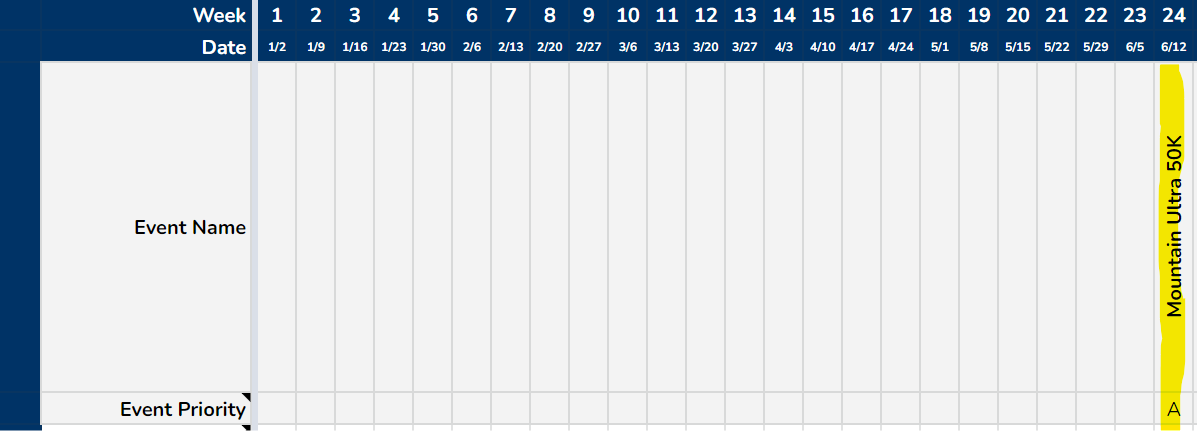

Write the name of your target event(s) in the row for Event Name; and below each event, in the row for Event Priority, write A, B, or C according to how you’ve prioritized them. Adjust the weeks/dates as needed to create an outline with the number of weeks from the start of your training plan to your last A-priority event of the season.

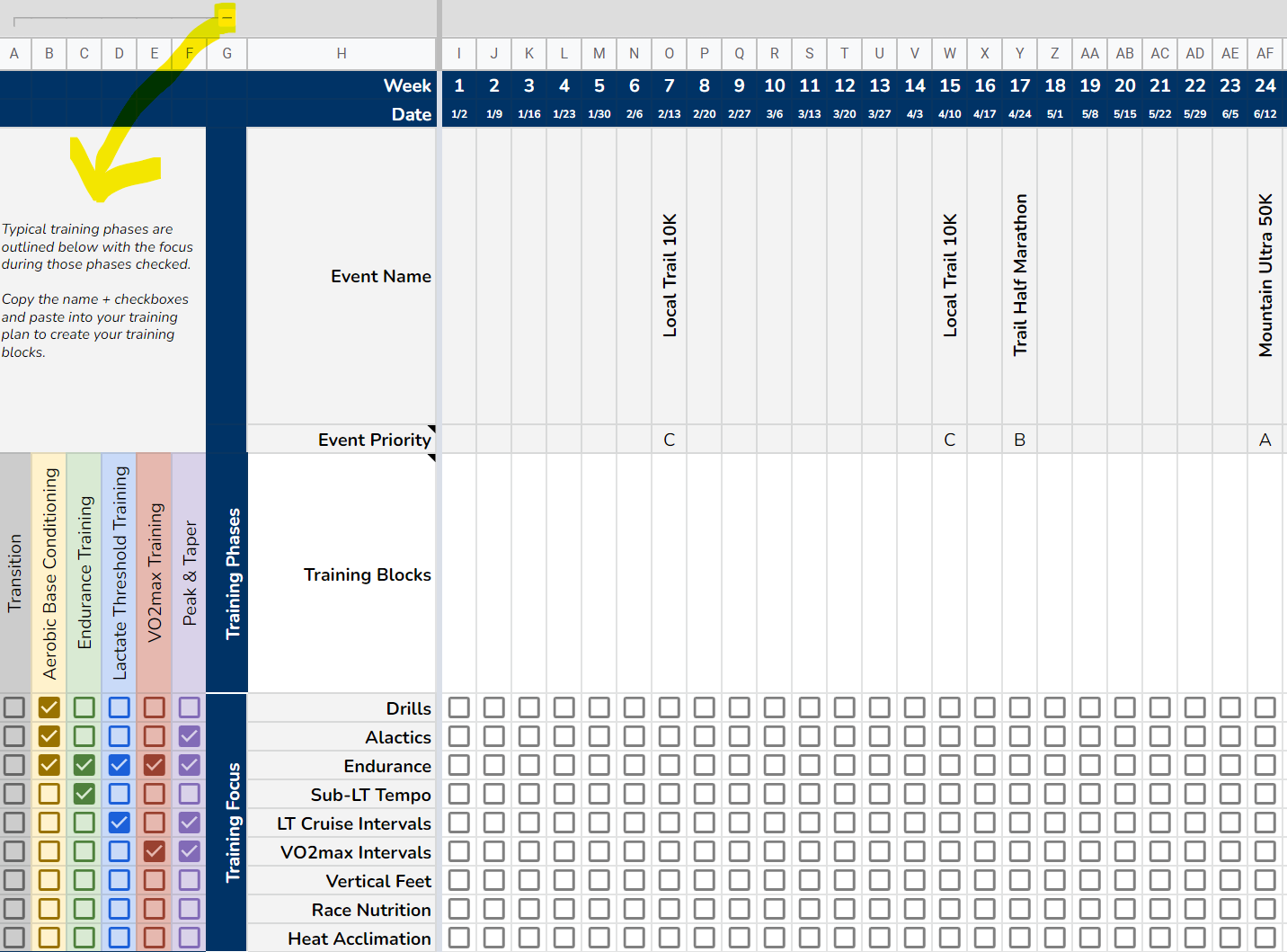

For example, in this demo, my target event is the Mountain Ultra 50K on June 18. I mark that as an A-priority event.

I also have a B-priority event — the Trail Half Marathon on April 30 — and some C-priority events that I will use as workouts: the Winter Trail 10K on February 19 and the Spring Trail 10K on April 16. I start my training weeks on Mondays and end them on Sundays, so the races occur at the end of the weeks where I’ve placed them.

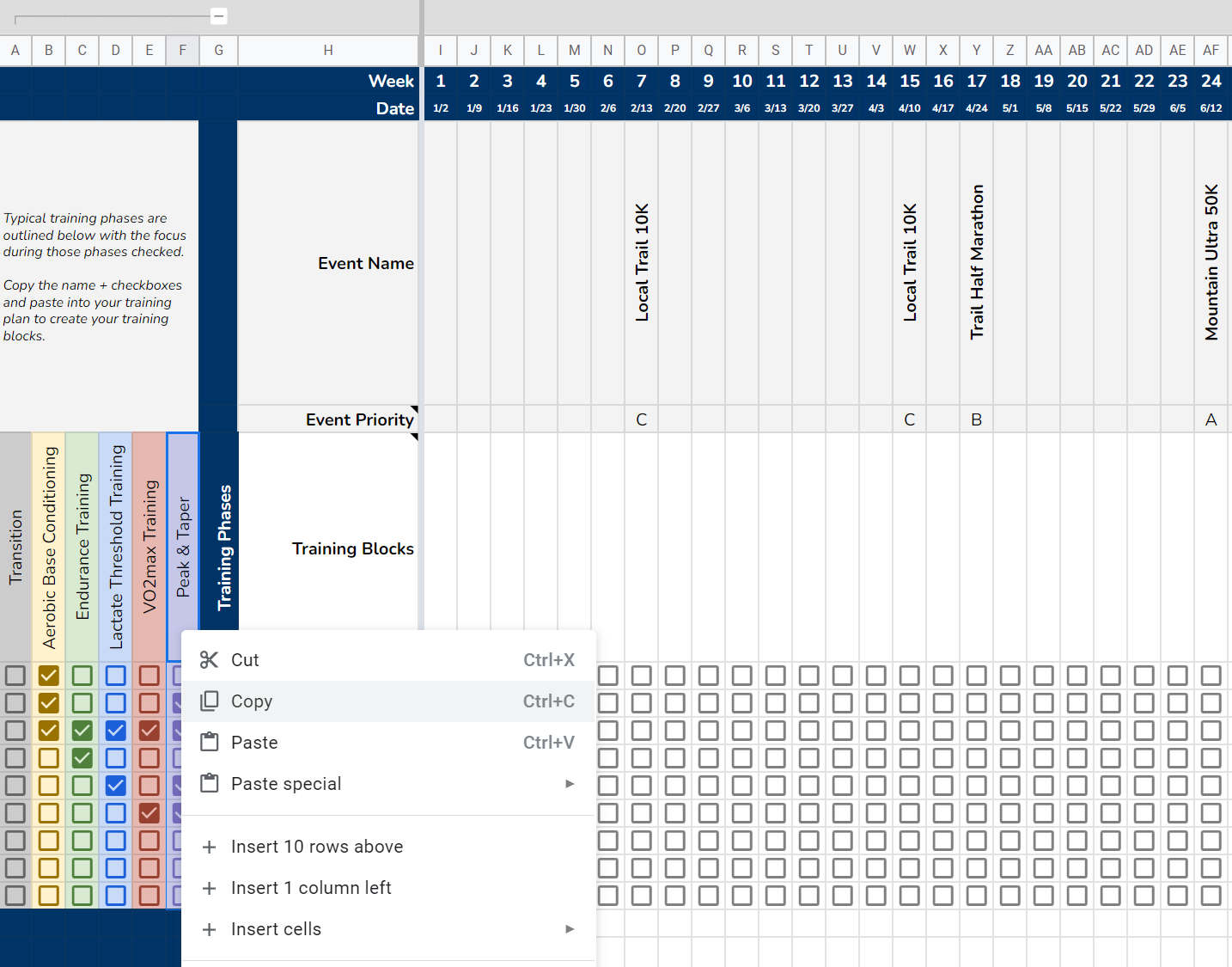

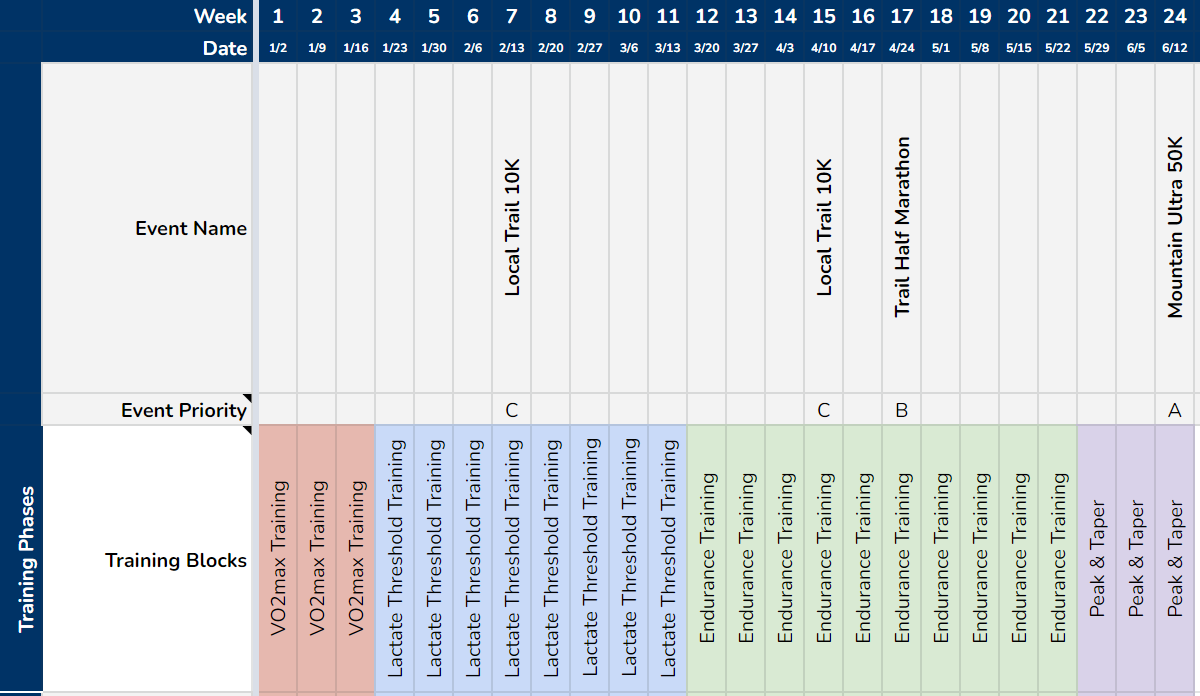

Now that you have your target event(s) on the calendar, work backwards to lay out the training phases. Notice that if you click the plus sign in the upper left of the Google Sheet, you can view columns A-F with the main training phases.

Below the training phases are checkboxes that indicate different elements to focus on. These include the key workouts for each phase, as well as other race-specific details to work on as you near your event — for example, this could include a focus on vertical feet (to match the profile of your race), dialing in your race nutrition strategy, acclimating to the heat (if you’ll be racing in hot weather), etc. Add additional rows here to capture what you may need to focus on for your particular event.

You can simply copy the name of the training phase, along with the checkboxes below it; then paste it into your training plan to map out your training blocks (or write in the names and check the boxes).

Start at the end with your final A-priority event and add in a Peak & Taper training block of 1-3 weeks. Remember, the longer the race, the longer the taper (up to three weeks). The shorter the race, the shorter the taper (maybe only a week).

For example, in this demo, I lay out a 3-week Peak & Taper prior to the A-race on June 17.

Decide how you will order the training phases and distribute them across the weeks of the plan, following the guidelines provided in the previous chapter.

- What will be your progression of training phases? For example, will you focus on Endurance Training or VO2max Training closer to your event?

- How much time will you spend on each training phase? Recall that training phases that focus on lower intensity work will be spread out over more weeks, while training phases that focus on higher intensity work will be fewer weeks.

- How will you structure recovery into your training blocks? For example, will you work in 3-week or 4-week cycles for recovery weeks?

For example, in this demo, I’m going to end my progression with Endurance Training since I’m targeting a trail 50K with a decent amount of elevation gain. My aim will be to focus on building my long runs and vertical feet during that final training phase. I’m heading into the training plan with a good base, so I will move right into VO2max Training > Lactate Threshold Training > Endurance Training > Peak & Taper.

This will be a 24-week training plan. So I will distribute each training phase as follows: VO2max Training (3 weeks) > Lactate Threshold Training (8 weeks) > Endurance Training (10 weeks) > Peak & Taper (3 weeks).

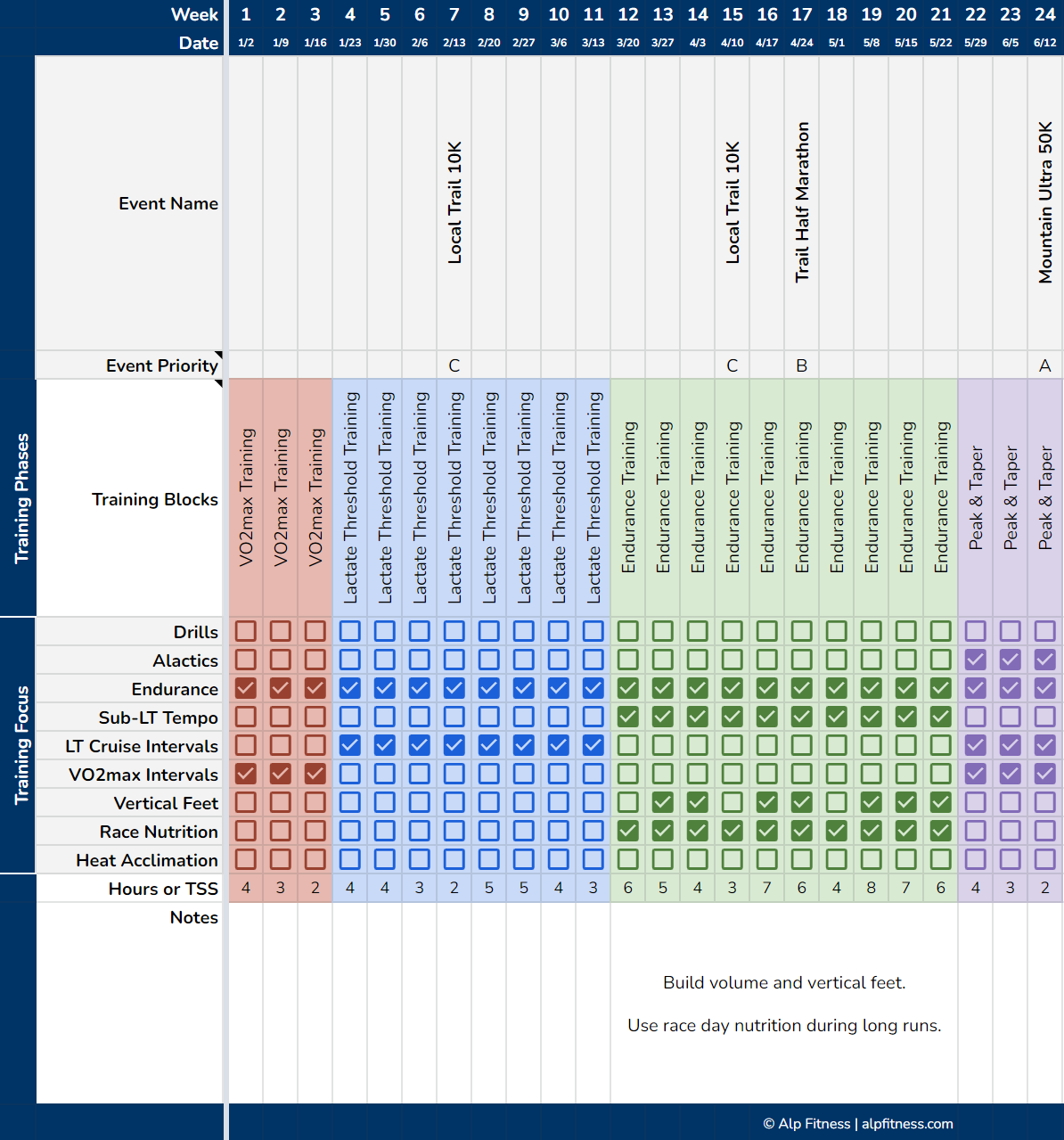

Next, assign a tentative training hours number or training stress score to each week in the plan. Setting these numbers in advance allows you to systematically plan out your training volume targets. This helps to avoid doing too much one week and not enough on other weeks. It doses out your training in a manner that allows you to consistently ratchet up your fitness.

- Training hours represent volume without taking into account intensity. So your training hours during higher-intensity blocks (VO2max Training) will be lower than hours during your lower-intensity blocks (Endurance Training). Training hours can be a helpful guide, especially as you seek to gradually increase your training volume and long endurance workout duration during the Endurance Training phase.

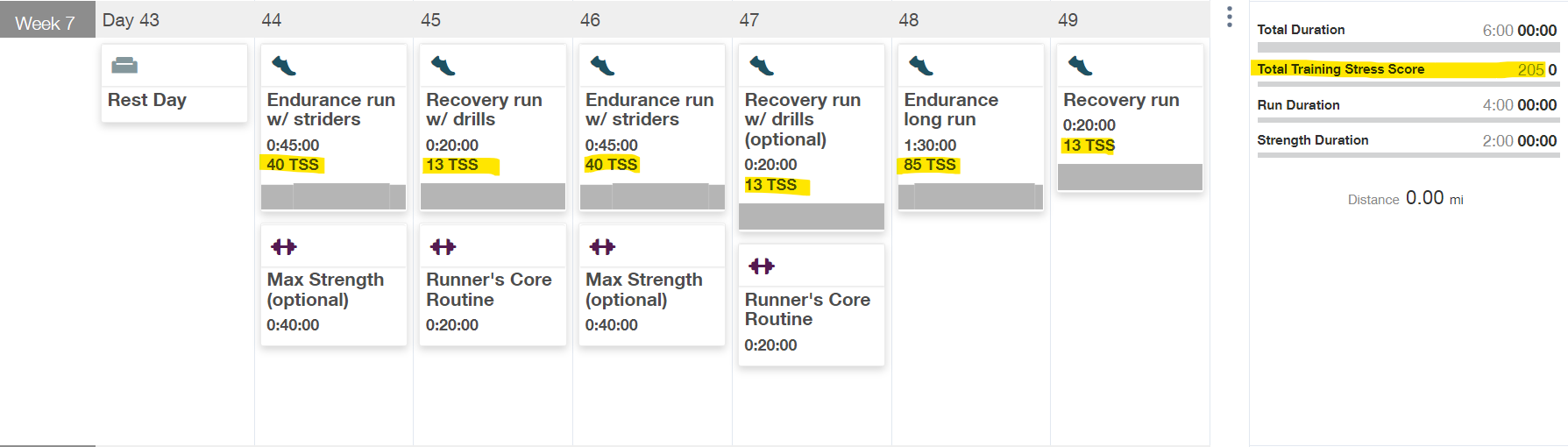

- Training Stress Score (TSS) takes into account both training volume and training intensity. It was developed by TrainingPeaks to help quantify training load. If you use TrainingPeaks; then you can see your weekly TSS total in the weekly summary, as highlighted in the image below.

Within each training block, focus on manipulating either volume or intensity, but not both at the same time. For higher intensity training blocks, such as VO2max Training, keep volume relatively constant while manipulating the intensity. For lower intensity training blocks, such as the Endurance Training, keep intensity relatively constant while manipulating the volume. This is where Training Stress Score (TSS) can become particularly helpful.

But whether you use training hours or TSS, setting these tentative numbers depends on your background and current fitness level. You must start from where you currently are and progress from there. Simply choosing training hours based on what someone else does or what you think you need to do for a given race distance overlooks your own unique situation.

Consider the average weekly training hours — or TSS — you put in over the previous season. That is your starting point. Then consider the average weekly training hours — or TSS — you will need to train to be successful in your target event. That is your destination. If the gap is too wide to accomplish in a single season; then you may need to approach your goal as a longer term project.

Although cramming for a long-distance endurance event (akin to staying up all night to cram for an exam in school) should be avoided, it’s also important to keep in mind that more training hours are not necessarily better. There is a sweet spot for you that you need to find, and you want to find it without pushing yourself over the edge into overtraining. That is where a smart training plan can help.

Ultrarunners use the minimum/maximum guideline as a reference point to understand how much training time is required to prepare for an event. Minimum refers to the minimum amount of hours you need to train during your highest — maximum — volume training phase, and when that should be in relation to your target event.

- If you’re training for an ultramarathon from 50K to 50 miles; then you want to target at least 6 hours per week over 3 weeks starting 6 weeks prior to your target event.

- If you’re training for an ultramarathon from 100K to 100 miles; then you want to target at least 9 hours per week for 6 weeks, starting 9 weeks before the goal race

This shouldn’t be taken as a one-size-fits-all prescription, but rather as a general guideline to help you realistically determine where you’re currently at with your training and where you need to be to set yourself up for success at your target event. It also underscores that training to complete an endurance event — even an ultramarathon — need not be a full-time job, which is good news since most of us have full-time jobs on top of the training we do. Unless you’re a pro, you will need to work your training around your work schedule and other life commitments. Be ambitious but realistic as you keep an eye on recovery to stay in that sweet spot — not too much, not too little.

In this demo, notice how I’ve arranged the training hours. I target fewer hours during the higher intensity phase VO2max block that starts the plan. This is important because I’ll be starting out with higher intensity intervals during that block and adding volume there would make it difficult to achieve that higher intensity work without putting myself in a hole.

I add a little bit of volume during the Lactate Threshold Training since the intensity of the intervals decreases. Then, I start to ramp up the training volume during the Endurance Training phase. Notice how the hours step down to recovery weeks throughout the training phases.

Also, the minimum/maximum guideline is met for the 50K distance of my target event — training at least 6 hours/week for 3 weeks starting 6 weeks out from the race.

The exact training hours each week will depend on how I’m recovering from the workouts, taking into account other life stressors that come along. But these estimates will provide guidance as I implement the plan on a weekly basis.

This sample plan is for one athlete. Your plan will look different because you will need to create it based on your own background and goals.

So that’s the sample training plan demo for a particular athlete targeting a particular goal. Use the same process to create your own training plan based on your starting point and desired destination.

Once you have a high-level training plan for your target event(s), view the plan as a blueprint, rather than a final document set in stone. You will write the final version over the coming months as you glean feedback from your training each week and adapt your training to your specific situation and goals.

The next and final step is to implement your plan by creating weekly schedules, which is discussed next.